This the first blog in our Understanding Drought blog series about the current drought in Alberta. Stay tuned to abwater.ca for blogs, videos, and up to date information. Cover image by Jon Martin. Blog by Maria Albuquerque. Edited by Jon Martin and Shannon Frank.

Read the rest of the series:

Actions and Consequences of Drought in the Watershed

Sharing the Shortage: A Collaborative Approach to Water Management

Celebrating Every Drop

Well, what about groundwater?

Building Resiliency to Multi-Year Drought workshop

Not So Cut and Dry: Spring 2024 Drought Update

Fall 2024 Drought Update: How Did We Fare?

The Oldman Reservoir's new sandy appearance indicates a low water supply throughout the Oldman watershed. The water at the Oldman Reservoir, one of ten in the basin, has reached close to its lowest storage level recorded since it was built in 1991. Signs of drought have persisted for the third consecutive year, with prolonged periods without significant rain and snowfall contributing to low water levels in more than 50 water management areas in Alberta—an increase of 20 areas since August. Although droughts are not new to our semi-arid corner of Southern Alberta, as we approach winter with record-low water levels, new challenges emerge. While the Government of Alberta has plans in place, the current water shortage can impact a range of our needs. Winter snowfall will be critical for next year’s irrigation season and for the overall health of the watershed, as our surface water mainly comes from snowpack.

Oldman Reservoir on October 21, 2023. Photo by Jon Martin.

Current Conditions

Since 2021, Southern Alberta has experienced dry conditions affecting our surface water levels. The Oldman watershed is one of the few watersheds in Canada that does not rely on glacier melt for its water supply. Most of our surface water originates from snowpack and rainfall in the mountains, flowing into the six major rivers—Oldman, Crowsnest, Castle, Waterton, Belly, and St. Mary—and their tributaries. Mountain snow runoff and precipitation levels have been below average for the past three years.

From spring to now

This spring, the ten reservoirs in the Oldman basin had an average storage level of 70% full capacity. The Oldman Reservoir was at 64% of full capacity, which was below average for that time of year and made summer precipitation even more critical. However, we did have sporadic days of rain, leading to an average of 59.1% full capacity in the reservoirs by August. It is normal to have lower water levels at the end of summer, but since we started the season with less water than average, we also finished with less.

Precipitation Departures Relative to Normal During the Past 3 Years. Southern Alberta had the lowest levels compared to average levels of precipitation in this region. Source: Government of Alberta.

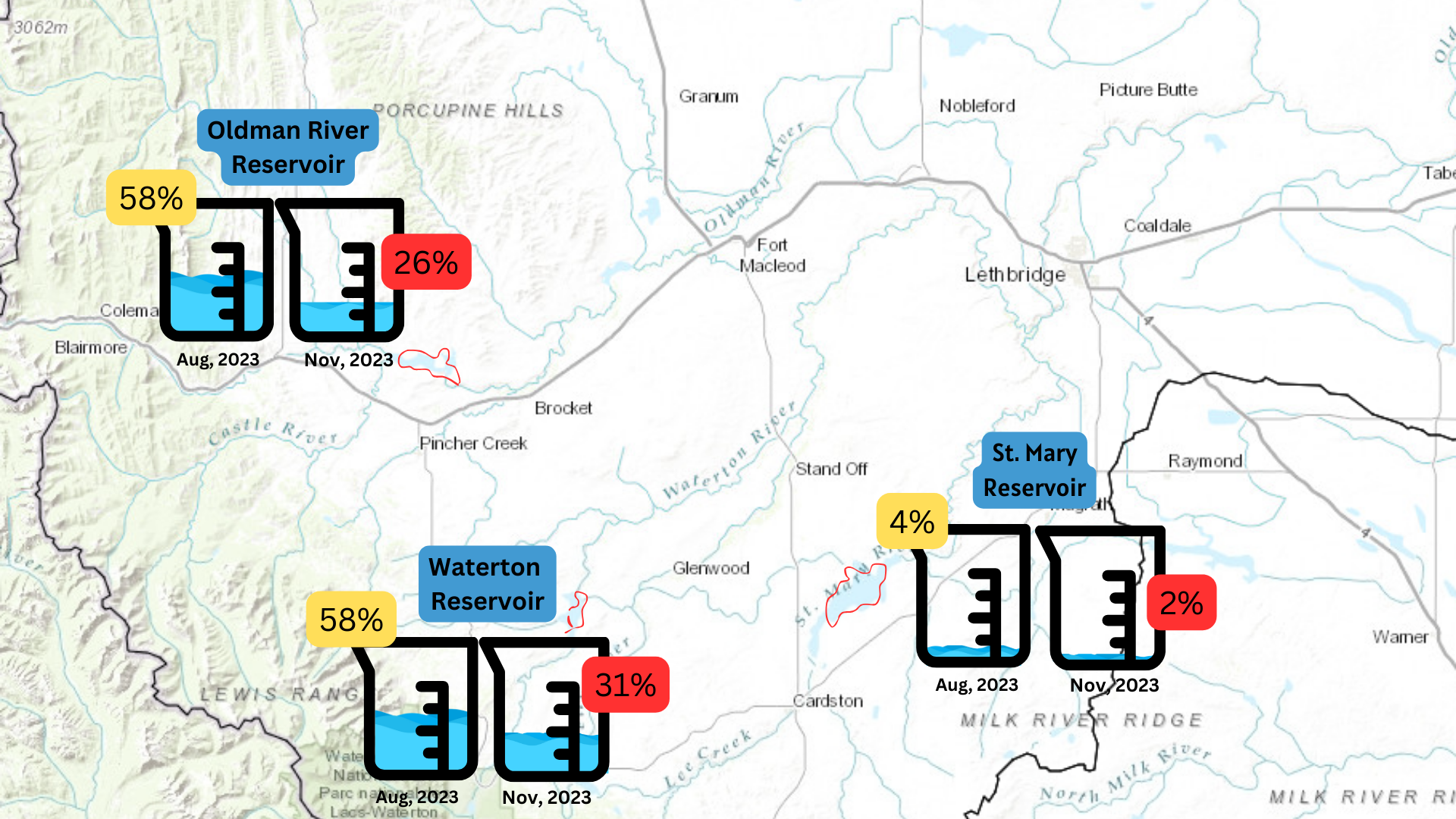

This fall, we experienced near-normal precipitation levels for September and October, which are typically dry months. The first major snowfall on October 21 helped improve soil moisture levels in Southern Alberta, but it did not increase water levels in the reservoirs or water flow in the rivers. In fact, the region remains in an exceptional drought, meaning this is the driest it has been in the last 50 years. As of November 29th, the Oldman Reservoir is at 26% of full capacity – significantly lower than the average for this time of year, which is around 60%. The average level in all ten reservoirs in the basin is 50.3%, with the St. Mary Reservoir being the lowest at 2%.

For the past three years, agricultural and natural areas have been impacted by soil moisture deficits, resulting in poor growth of native and cultivated crops. While these figures underscore the urgency of a wet winter and may sound alarming, we are not yet at risk, and the Government of Alberta is closely monitoring the drought with plans in place.

The water levels in the three major onstream storage reservoirs in the Oldman watershed (Oldman, Waterton and St. Mary Reservoirs) comparing August 2023 to November 2023. November volumes are much below average for all three reservoirs, and the lowest it has been for the Oldman and St. Mary Reservoirs.

Since July 2023, Southern Alberta has been under Provincial Water Shortage Management Stage 4 as a drought response by the Government of Alberta. The final stage, Stage 5, includes the option to declare a state of emergency. Stage 4 is enacted when a significant number of water users in multiple water management areas are affected, unable to divert water, and the water shortage is projected to continue. The number of Water Management Areas under a water shortage advisory has increased from 31 to 51 across the province, with more than 15 in the Oldman watershed. Under Stage 4, the provincial government may convene key stakeholders to develop a water shortage strategy that meets interprovincial obligations (sending 50% to Saskatchewan), as well as the needs of water users and the aquatic environment. A snowy winter is crucial to restore water levels next year and to avoid escalating to Stage 5. By April 2024, the Government of Alberta will have a better estimate of snow accumulation, which will inform the appropriate water management steps for the upcoming season.

Looking Ahead

What a(drought) Winter?

Winter snowfall plays a key role in our water supply for people and ecosystems. Water volume depends on both the depth and the density of the snowpack, particularly in the mountains where our rivers originate. A wet winter with significant snowfall will be critical, but the forecast is not yet clear. According to the Environment Canada seasonal forecast issued on October 31, 2023, precipitation is expected to be normal for Southern Alberta. However, El Niño warming and dry patterns have already been experienced in many cities across the Prairies.

Climate Patterns

Recent findings by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration confirm that El Niño warming patterns have contributed to a warmer and drier year so far. The upcoming seasons—winter, spring, and early summer—are also expected to be drier, with temperatures higher than normal. Climate trends indicate that the Prairies may face prolonged and intensified drought conditions over the long term. Furthermore, spring snow cover across the Northern Hemisphere is projected to decrease by 7%-25% by the end of the 21st century.

El Niño causes the Pacific jet stream to move south and spread further east. During winter, it contributes to warmer and drier conditions in the north of North America. Source: NOAA, 2023

Winter drought, characterized by lower-than-average snowpack, typically occurs during above-average temperatures. This type of drought affects snow accumulation: snow may melt earlier in the season, and precipitation is more likely to fall as rain rather than snow. Insufficient snowpack can diminish water availability in both summer and winter, posing significant challenges for current and future water management and supply.

What Does This Mean For Our Current Needs?

The Oldman River and its tributaries supply water to many local communities, irrigation districts, livestock, and industries. Continuing downstream, our watershed also delivers water to Medicine Hat and beyond into Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and eventually Hudson Bay. A water shortage impacts all water users from here to there!

Many municipalities source their water from surface sources, such as rivers, which involves an intake pipe—a structure that diverts water from a waterway. Imagine it like using a giant straw to suck up water. Lower water levels in winter are at a higher risk of freezing, making the extraction of water from frozen streams as challenging as trying to suck water from a cup of solid ice. While some municipalities have winter storage, a winter drought can place some communities at risk of not having sufficient water access. Even in the absence of ice, low water levels can cause problems, as exemplified by the Municipal District of Pincher Creek, which has been unable to pump water into its intake pipe since August 2023. The City of Lethbridge is taking proactive steps to maintain access to water during times of low flow.

In addition to municipal water use, farmers, food processors, and manufacturers also require a consistent water supply throughout the year. Although the demand for water in agriculture decreases in winter because crops no longer need irrigation, livestock still need drinking water. For example, an adult cow typically needs to drink between 22 to 56 litres per day. Icy conditions in waterways can hinder how farmers access and store this water. The food processing and manufacturing industries in Alberta’s Premier Food Corridor are also dependent on water for their operations. Ultimately, low water flows combined with freezing temperatures could affect not only our personal water usage but also various sources of food and income, as well as the aquatic ecosystem.

Low water flow heightens the risk of fish kills. With less water available, fish and other aquatic organisms face increased competition for the limited oxygen supply, even before bodies of water become encased in ice. These reduced water levels can render conditions uninhabitable for fish. In our next blog, the OWC’s professional biologist will delve deeper into how winter drought affects the ecosystem of the Oldman watershed.

Photo credit: Maria Albuquerque

All We Want For Christmas is… Snow!

To summarize: Low water levels throughout Southern Alberta affect the water supply in the Oldman watershed and neighbouring basins. In response to this, as part of Stage 4 of the drought response, the Alberta Government collaborates with irrigation districts, local governments and other water users to conserve and manage water across more than 50 water management areas in the province. Although it's difficult to predict the winter season, El Niño patterns suggest a warmer and drier winter, which could increase the likelihood of a winter drought and result in lower water levels for spring and summer. This potential winter drought might affect the water supply for municipalities, farmers and livestock, industries, and aquatic ecosystems. While we hope for a snowy winter, we can collectively work to reduce water consumption, stay informed, and implement strategies to mitigate the effects of a prolonged drought.

To keep up to date on the drought situation visit abwater.ca, where OWC will be providing new information regularly.

Oldman River near Piikani Nation. October 27, 2023. Photo by Maria Albuquerque.

Banner Photo credit: Jon Martin